Let's Fail

- Douglas Abrams

- Apr 24, 2025

- 13 min read

Most people are afraid to fail because at some level they equate failure with death. This fear is encouraged during their education, as receiving an F in school is like academic death: final, unrecoverable and to to be avoided at all costs. Fear of failure is further fostered after graduation, in organizational work environments where failure is often severely punished.

However, to succeed as a scalable entrepreneur, you must strive to fail. Embracing failure is the most important mindset change you need to develop to succeed in an entrepreneurial career (or in the NBA).

Michael Jordan put it this way: “I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

Striving to fail

Examining the range of views that people hold about failure in Southeast Asia, I have found that they fall into three main categories. First, the “Traditional” view can be summarized as: “Failure is bad and should be avoided at all costs.” This traditional view of failure was one the factors that in the past held back Singapore and other parts of Southeast Asia from success in scalable entrepreneurship. Aversion to failure is sometimes conflated with risk aversion, as in the mistaken view that “Asians are risk averse.” If Asians are risk averse, why is gambling so popular in Asia? Risk-averse people do not like to gamble, as love of gambling is the antithesis of risk aversion.

There is a higher level of failure-aversion (versus risk aversion) in SEA than in the U.S., for example. However, even the Southeast Asian view of failure is rapidly evolving. When I first came to Singapore in 2000, a fairly large percentage of people would have agreed that failure was bad and was to be avoided at all costs. There were significant legal, financial and reputational penalties for business failure and bankruptcy.

Today, most people would agree with the “Mainstream view” that “Failure is acceptable insofar as it leads to learning.” Singaporean business failure and bankruptcy laws have been liberalized, and some well-known failed local entrepreneurs have even gone on the lecture circuit to talk about the lessons they learned through failing. This would have been unimaginable when I first arrived in Singapore.

The view of failure that is required of successful scalable entrepreneurs is the “Entrepreneurial” view: “Failure is desirable.” To become a successful scalable entrepreneur, you must strive to fail.

Why is failing good for entrepreneurs?

Firstly, scalable entrepreneurs must strive to fail because willingness to risk failure allows them to take the necessary level of risk required to succeed big. High risk ventures, the kind that generate the high returns that comprise scalable entrepreneurship, are highly likely to fail.

Failure is necessary for innovation

There is a second, and equally important reason that scalable entrepreneurs need to embrace failure: the relationship between innovation and successful scalable entrepreneurship. Innovation, in one form or another, is a fundamental component of scalable entrepreneurship and failure is a fundamental component of innovation.

Why is failure so important for innovation?

Innovation is a trial-and-error process. Successful innovations do not happen on the first try. The “error” in trial-and-error means that the road to successful innovation is paved with failure. Disruptive innovation is likely to fail big before it succeeds in changing the world.

Why do we always overestimate short-term and underestimate long term change?

The reaction to innovations, especially disruptive innovations, follows a highly predictable path.

Skepticism

Irrational exuberance – huge overestimation of short-term impact

Irrational disillusionment – huge underestimate of long-term impact

Acceptance

Here is an example for the internet:

“The internet is just good for porn” – 1994

“The internet is going to change everything, now” – 1998

“The internet was just an investment bubble” – 2001

“The internet has now changed everything, much more than we could ever imagine in 1998” – 2020

More recently, reactions to AI, Blockchain and crypto have followed a similar pattern. Why do we keep getting this so wrong and getting it wrong in the same way?

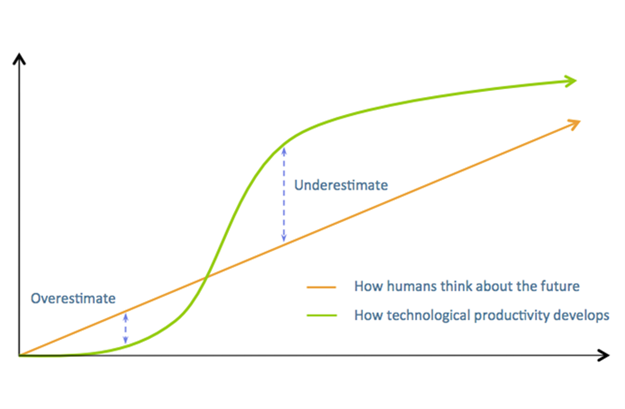

We get it wrong because technological change follows an exponential curve, but we always expect change to follow a linear curve. It makes sense that our minds are tuned for linear change, as almost all the change we observe in our day-to-day lives is linear. Our kids get older one day at a time, grow a little taller each month, progress through school one year at a time.

But disruptive technologies do not grow like that. They typically have a long early period of slow growth, then they hit an inflection point, then they grow exponentially, then their growth levels off, then they are supplanted by the next generation disruptive technology. If we graph this pattern it looks sort of like an “S”.

If we look at a linear growth curve, which forms a 45-degree angle, versus an exponential growth curve, we can see why we always overestimate the growth of a new technology in the short run and underestimate it in the long run.

Linear growth exceeds exponential growth in the short run but way underperforms in the long run. There is even a name for this phenomenon – it is called Amara’s law.

The rate of technological change is increasing exponentially

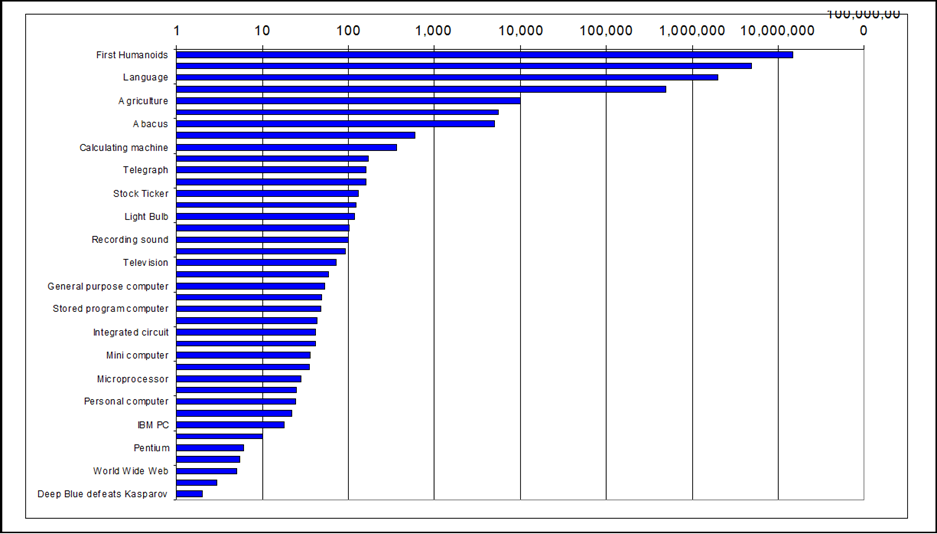

It is not just individual innovations that develop along an exponential curve. The rate of technological innovation itself is increasing exponentially.

This means that we need to move ever faster to keep ahead, and therefore be ever more willing to take risks that will lead to failure.

The chart above is of technological progress over time -- beginning with one of the first known technologies and ending in 1997. The scale is logarithmic, so when you move along the x-axis by one unit, the time measured increases by 10X. To see just how much the rate of technological change has increased, let’s consider a technology near the top of the chart: the stone axe. Stone axes are considered by archaeologists to be among the first known human technologies.

To construct a stone axe, you take one stone, and you use it to chip away one side of another stone, so that the first stone becomes sharp on one side. It sounds very simple, but in fact the technique is quite sophisticated, and the resultant tool was a tremendous technological advance at the time.

Stone Axe (and other early tools) v1 – 3.3 million years ago

Stone Axe v2 – 1.76 million years ago

When you look at the archeological record of stone axes, you find that the initial design remained unchanged for hundreds of thousands of years, until a prehistoric innovator finally created stone axe version 2; by sharpening a stone on both sides. You might call this the first known technological innovation of an existing product. The time between versions one and two was several hundred thousand years.

If you look further down the chart, you can see that it took only about 40 years from the development of the first digital computer (which you can still see at the University of Pennsylvania – it is the size of an entire room and had less processing power than the first iPhone) until a computer beat Gary Kasparov, then the world champion, at a game of chess. Now less than 30 years later, we are on the verge of AGI.

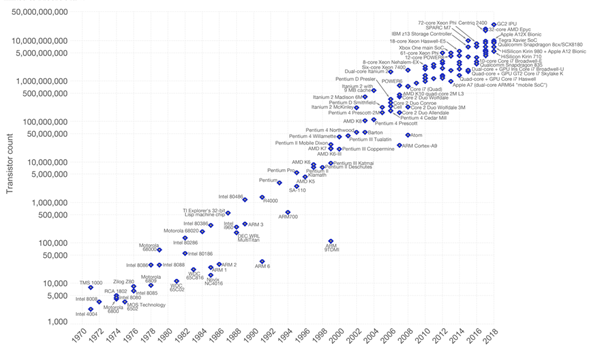

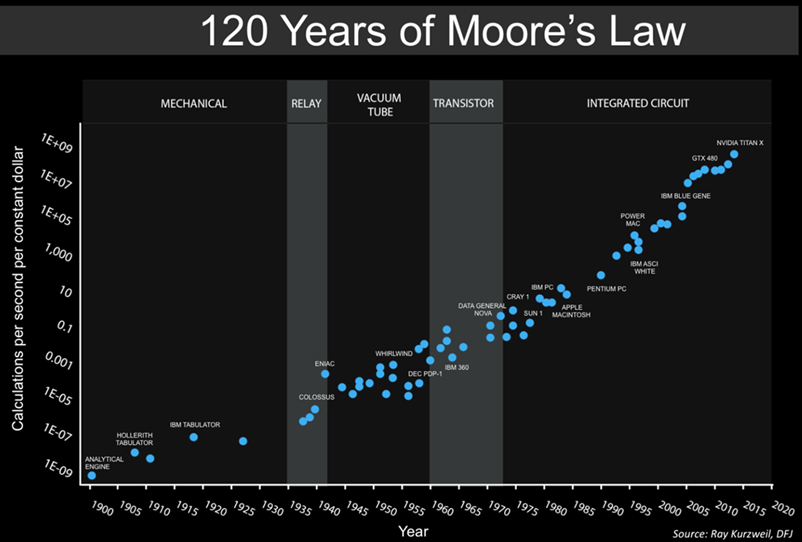

Moore’s Law and the rate of technological innovation

Moore’s law, formulated in 1965 by Gordon Moore, one of the founders of Intel, is a well-known example of the exponentially increasing rate of technological change. Moore predicted that the number of transistors on microprocessors would double approximately every 24 months, and although the exact rate has varied, the number of transistors has grown exponentially for many years. The Intel 4004 chip released in 1971 had 2,250 transistors. In 2025 Apple's M3 Ultra SoC consumer microprocessor has 184 billion transistors while the Cerebras Wafer Scale Engine 2 (WSE-2), a specialized AI and machine learning processor, contains 2.6 trillion transistors.

When the IBM 360 computer was released in 1964, the top model came with eight megabytes of main memory and cost more than $2 million. In 2025, handphones with 8,000- 16,000 times the memory of that computer can be bought for about $200 – 0.00001 of the cost.

This exponential rate of change does not only apply to microprocessors: in 2001, Rob Carlson, then a research fellow at the Molecular Sciences Institute, in Berkeley, California, decided to examine a similar phenomenon: the speed at which the capacity to synthesize DNA was growing. He produced what has come to be known as the Carlson curve, and it shows a rate that mirrors Moore’s law—and has even begun to exceed it. The cost of sequencing a human genome has fallen from $100 million in 2001 to around $200 in 2025.

Isn’t Moore’s law over?

Some people now predict that the increase in the rate of technological change is going to slow as we reach the limit of transistor doubling on ICs, as the size of these transistors shrinks to the size of silicon atoms, after which it will be impossible to squeeze more onto a silicon-based IC.

But Moore’s Law does not apply just to silicon-based ICs; rather it is a function of the cumulative nature of technological change, with each generation of technology building on the previous generation, as we can see in the graph below showing 120 years of exponential growth in information processing technologies, beginning well before the invention of silicon-based ICs.

The future rate of technological change is not likely to slow; it is likely to continue to increase, and potentially much faster in the not-too-distant future, especially given the growth of AI.

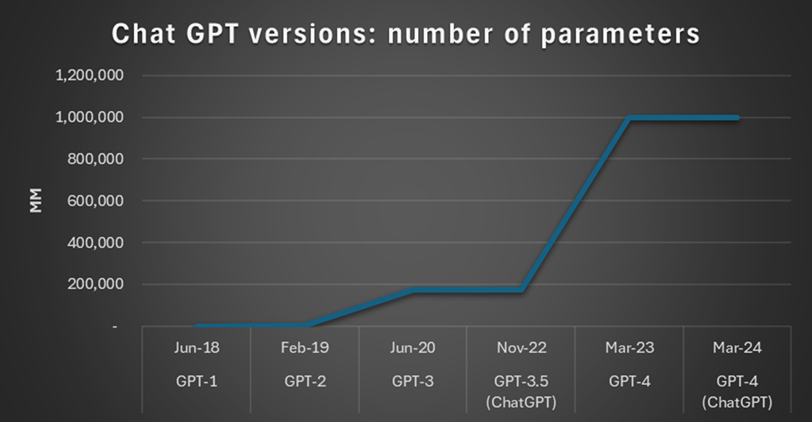

For example, Chat GPT performance increased 8500X from 2018 to 2024:

When AI technology gets to the point where it can design and produce the next generation of AI technology itself (often referred to as the singularity), the rate of technological change will advance at speeds unimaginable today.

Attitudes toward failure

To be a successful scalable entrepreneur, you must innovate. Innovation requires failure. You succeed at scalable entrepreneurship by trying, failing, and trying again. If you are not failing, you are not trying hard enough.

Some of history’s best-known innovators have shared this attitude toward failure:

“An inventor fails 999 times, and if he succeeds once, he’s in. He treats his failures simply as practice shots.” - Charles Kettering - founder of Delco and inventor with 200 patents

Failure is “the opportunity to begin again, more intelligently” - Henry Ford, who started Ford Motors after failing at 2 previous ventures.

“The fastest way to succeed is to double your failure rate” - Thomas Watson, founder of IBM.

“Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.” - Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft.

Post-It notes: failure spawns an innovation

Sometimes there is an even more direct relationship between failure and innovation; situations where failures spawn innovations. One of the most famous examples of this relationship is 3M’s Post-It notes.

The Post-It Notes story began with an engineer at 3M who was trying to formulate a stickier glue. Normally the stickier a glue, the better it is. This engineer tried many different formulations in his search for a stickier glue, but the results were not good. The end product of his research was a glue that was not at all stickier; it was tacky rather than sticky, meaning that it barely held two pieces of paper together.

After the failure of this project, the engineer wrote and circulated a long memo to the other engineers in his department, describing his project failure (this was before email; people still sent paper memos).

In this seemingly simple act, we can see one of the reasons that 3M is one of the most innovative large companies in the world. Think about this for a second: if you have ever worked in a large organization, what did employees do when a project they were working on was a total failure? Did they write a memo (or email) and send it to the rest of their department describing how they had failed? You bet they didn’t. In most large companies, employees would rather have hot needles driven into their eyes than circulate memos highlighting their failures. If such a memo did happen to get written and printed, you could be sure that the employee in question would attempt to lose it behind the biggest, heaviest file cabinet in the office in the hope that it would not be discovered until the company was sold and moved to a new building. Not so at 3M, where failure is actually encouraged.

Fast-forward to another 3M engineer who was experiencing a problem in church. The hymnal that contained the songs sung during the church service did not list the songs in the order in which they were sung and also contained songs which were not used in the service. He was new to this hymnal, so whenever he stood up to sing, he had to leaf through the book to find the proper page for the song, and by then he was behind everyone else and had to catch up. He would have loved to mark the pages of the book with the songs that would be sung during each service so he could turn quickly to the proper pages, but he couldn’t figure out a way to do that. He couldn’t bend down the corners or write on the pages because it was not his book. He tried inserting pieces of paper into the pages, but when he stood up and opened the book, all the papers fell out. What he needed was a bookmark that could actually stick to the pages of the book but be removable without damaging the page. And then he remembered…the memo about a tacky but not sticky glue. What if he applied some of that glue to the edge of a piece of paper to make a removable bookmark? The innovation that became Post-It Notes was born. (We also see how innovations that solve problems can be very powerful – this is called a “value proposition”).

This story often triumphantly ends here, but there is a twist. The engineer then pitched his innovation to 3M management, who did not at this point see the potential in the product and decided not to pursue it, as they felt a removable bookmark was not a very interesting product (and they were partially right). But the engineer believed so much in the potential of the product that he produced prototypes using his own money and distributed them to secretaries around the 3M office. Soon he learned something very interesting about his own innovation. The secretaries did not use the slips of paper as removable bookmarks. They mostly used them to write notes on and then to stick the notes all over their desks (which is why lean start-up methodology advises you to “get the product into the hands of potential customers as early as possible”). And thus, was born from a research failure, the Post-It Note, one of the most successful innovations in the history of 3M.

It is not just products that can become successes from failures. One of my favorite examples of successful failures is Albert Einstein, who in 1895 failed the entrance exam to the Swiss Polytechnic, a top technical university. In 1902, unable to find work at a university, he took a job as a clerk at the Swiss Patent Office. Three years later, he submitted his famous paper on the Special Theory of Relativity to a leading German physics journal, and at the age of 26, formulated the equation, e=mc2, went on to win the Nobel Prize, and now is recognized as one of the leading thinkers of the 20th Century, if not of all time. And Einstein is not alone. History is full of this kind of successful failure: U.S. Grant, Henry Ford, Charles Kettering and Winston Churchill are a few notable examples.

People who never fail are not trying hard enough, are not stretching themselves, are not taking enough risk. The ones who succeed the biggest also tend to have failed the most.

How many times did Steve Jobs and Apple fail?

For entrepreneurs, two of the best role models of successful failure must be Steve Jobs and Apple. This may seem shocking, as I guess if I were to ask you to name the most successful entrepreneurs and most successful starts-up in the last 40 years, Jobs and Apple would be pretty high on most people’s lists, especially given that Apple today is one of the most valuable and profitable companies not only in the world, but in the history of the world. But this out-size success was built on a foundation of repeated and large-scale failure.

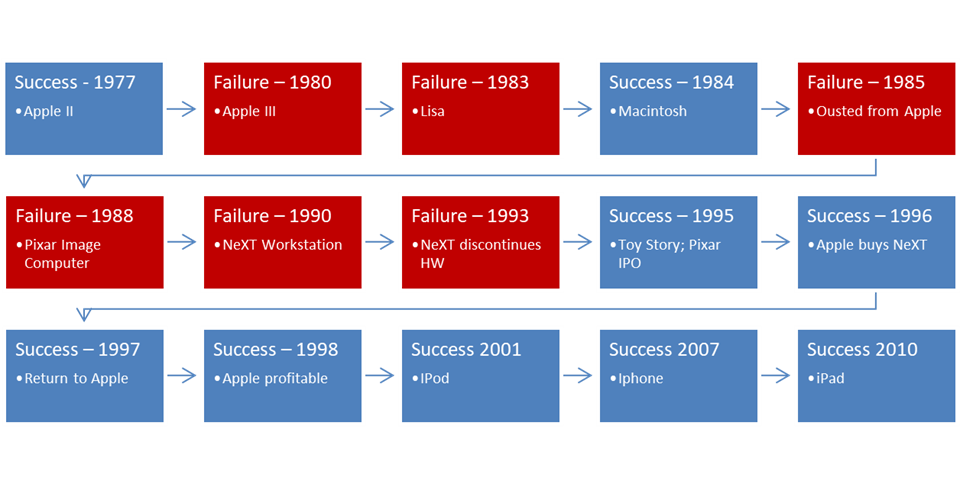

The timeline below illustrates Steve Jobs’ career successes and failures, with the successes in blue and the failures in red

After an initial success in 1977 with the Apple II, and a reasonable success with Macintosh in 1984 (a success for Apple; Jobs was ousted from Apple shortly thereafter), Jobs basically did not have a major career success for 18 years, from 1977 to 1995. During these 18 years he presided over one failed product after another, some at Apple and some in his own ventures, always in search of the next big thing:

1980 - Apple III - 75k units sold

1983 – Apple Lisa - 40K units sold in 1984 vs. 80K forecast

1986 – Pixar Image Computer - < 300 units sold

1990 – NeXT workstation – 50K units sold

1993 – Newton – 100MM spent on development – 80K units sold

Apple clones, NeXT software

Some of these were great products: I had a NeXT workstation and a Newton when I was at JP Morgan, but neither one was a commercial success.

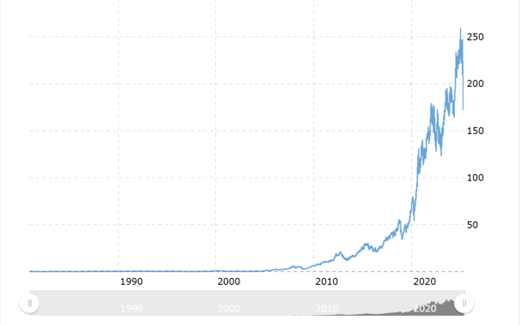

Over this same period of time, Apple shareholders were sitting out the dot-com boom as Apple’s share price declined from $53 per share in 1991 to $13 per share in 1998, losing 75% of their value.

For many years Apple fought a losing battle against its nemesis, Microsoft, in the PC market:

1980 – Apple’s share of PC market 15%

1996 – Its share had declined to 4%

2005 – Nearly 10 years later it had declined further to 2.2%

2011 – Microsoft Windows had a 92% share of operating system market

2025 – Microsoft Windows still has a 72% share of operating system market

Most of the company’s history and most of Jobs’ career were characterized by product failure, failure in the stock market, competitive failure.

Until it wasn’t.

Pixar animated films – launched 1995 (Toy Story), 18 Oscars, 10 Golden Globes, 11 Grammys, Films have earned > $17.1 billion worldwide.

iPod – launched 2001, 90% market share by 2004, 450 MM units sold worldwide through 2022.

iPhone – launched 2007, 2.5 billion units sold through 2024, accounting for more than $200 billion in revenue in 2024 and 19% of the global smartphone market.

iPad – launched 2010, 600 MM units sold through 2024; 39% share of the global tablet market.

Jobs and Apple disrupted four product categories: animated films, portable music players, smart phones and tablets, and went from a perpetual failure to the most profitable company in the world, as reflected in their stock price from 1980 to 2025.

If that is not success from failure, then what is?

It is not a coincidence that one of history’s most successful entrepreneurs and start-ups rose from the ashes of repeated massive failure. Failure and success are inextricably entwined in entrepreneurship.

Failure is just tuition

If an entrepreneur does not strive to fail, he will not be willing to take the risk necessary to create a successful scalable startup. He will not set his goals high enough. He will not be willing to take the risk that is necessary for innovation.

There are some investors in Silicon Valley who will only invest in entrepreneurs who have already failed. As one successful start-up founder said, “I got my education on the mean streets of Silicon Valley, where I got to see how huge mistakes are made. Knowing what doesn’t work is perhaps more valuable than knowing what should work. Failure is just tuition. If you are in a failing start-up, take notes.”